SUNNY CAL JOURNAL - WV WRITER JIM COMSTOCK LITTLE NOTED NOR LONG REMEMBERED

By Bob Weaver 2022

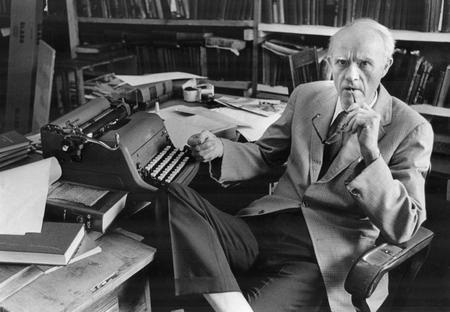

In today's overloaded media world, it would be easy to overlook West Virginia's illustrious Jim Comstock, publisher of the "West Virginia Hillbilly," a weekly publication from Richwood, which had a run of 30 years or more, and over 30,000 paid subscribers.

It would be fair to say, his monumental work is little noted nor long remembered.

The Saturday Review called Comstock's writing "Sophisticated," after which he requested a retraction.

Comstock devoted 20 years (1957-1977) to compiling the West Virginia Heritage Encyclopedia which included original content as well as reprinting long out-of-print material by and about West Virginians.

He led a campaign to preserve the house in Hillsboro where Pearl S. Buck, the Nobel Prize-winning novelist, was born. Comstock assisted with the financing of the rescue of the historic Cass Scenic Railroad. He also started the Mountain State Press to publish books of West Virginia interest.

Comstock wrote numerous books, while others published his creative endeavors,

A 2016 tribute published in The Paris Review, asserted that The Hillbilly wasn't just a paper, it was an art project, a platform for historic preservation, a conservative wailing wall, and, above all, an exploration of the West Virginian id, creative writing at its best.

In 1957, Comstock perpetrated an elaborate hoax involving the use of a captive mountain lion, to convince rival editor Calvin Price of neighboring Pocahontas County that these animals still existed in West Virginia. (After the exposé, he arranged for it to live out its retirement at the French Creek Game Farm, a state-run zoo)

In a notorious episode of pranksterism, Comstock once printed an issue of the Hillbilly using ink mixed with the juice of the ramp, the storied wild onion that abounds in the state in the spring. The intolerable stench at the local post office prompted the postmaster to extract a promise that he would never do it again.

I first heard about Comstock in the late 1950s, he appearing on WORs 50,000 watt (New York) "Long John Neville Show," a late night talk show, he going to the big city to promote his backwoods newspaper. Shortly after, I was a life-long subscriber.

The late Jack Cawthon, my writer friend of 60-years, was at times associated with Comstock's Hillbilly, often wrote about the lack of appreciation the rural town of Richwood had for Comstock's enormous endeavors.

Only a couple dozen locals actually subscribed to "Hillbilly," and the 21st Century recognition signs welcoming folks to Richwood honors a high school football player.

Cawthon wrote about a return trip to Richwood, "I had hoped to find Jim's spirit somehow in the descending mists that quickly shroud remembrances once we are dead. People all too soon forget a man such as Comstock whose unique contribution not only to journalism but to the state's heritage was of the greatest."

Returning to Richwood after the 2016 flood, I could not find a single person who extolled Comstock's virtues, but one hit it on the head by saying, "Writers are a dime a dozen."

Perhaps the lack of appreciation for Comstock in his hometown was his piece on "The Sexual Behavior of the Richwood Female."

I first met Comstock in the 1960s, being ask to drive to Charleston to meet him and drive the crooked road to Spencer, he being a speaker for a Farming for Better Living dinner in the Grace community. Comstock slid into the back seat, apologizing for his continued work with pen and a yellow legal pad, speaking rarely.

Returning to Charleston he continued to work with a flashlight on a swivel attached to a clipboard, although we did discuss our mutual friendship with Cawthon. I was disappointed about our lack of conversation, but we made up for it years later.

Comstock often praised Cawthon's writing, acknowledging Cawthon's life-long dream of becoming a famous creative writer, a dream he held to his death. Cawthon, who wrote a masterful column "Cawthons Catharsis" for the Hur Herald, often expressed his frustration.

I would respond to him, regarding my writing skills, that I had very low expectations, calling myself a "hack," rarely editing my stories for proper grammar or form.

On long, dreary days I go to the garage and retrieve boxes of yellowed copies of the "Hillbilly," to re-visit Comstock's writings or revel in the long-time work of Charleston's L. T. Anderson or Huntington's Dave Peyton, while reminding myself - "So empty is the glory that the world sparsely gives" to writers.

Many of Comstocks most fascinating stories appears in Otto Whitaker's book "The Best of Hillbilly."